For those whose life brought them to this camp, they look forward to the next time while wishing they could stay longer. They also wish they weren’t here in the first place and would trade the feeling of being here for having their loved one around them again. How can two opposing emotions exist at the same time?

Love, the strongest force that ever existed. Dutch resistance hero and writer Corrie Ten Boom (The Hiding Place) says it best on how:

“Do you know what hurts so very much? It’s love. Love is the strongest force in the world, and when it is blocked that means pain. There are two things we can do when this happens. We can kill that love so that it stops hurting. But then of course part of us dies, too. Or we can ask God to open up another route for that love to travel.” – Corrie Ten Boom

As I learned from my interview and discussion with the founder of Comfort Zone Camp, Lynne Hughes, on how her grief became a purpose for children grieving, the wisdom of Corrie Ten Boom holds true. The lives of Lynne’s parents, and all the loved ones who have graced the lives of campers at Comfort Zone Camp for 25 years, their love has found another route to travel, and the pain has been rewoven into a higher purpose, namely, to empower children experiencing grief to fully realize their capacity to heal, grow, and lead more fulfilling lives. She knew from her journey of losing both her parents that there was a need to make childhood grief a better journey than she experienced, and there are plenty of messages on camper-signed t-shirts from camps past to know that lives are being transformed.

From my discussion with Lynne (linked above), the genesis for Comfort Zone Camp came during her camp experiences as a child in the summer:

“As a grieving child, she was crying for help yet wondered who was listening. What helped during her childhood years to escape this reality of her life were people that did care. She found them at summer camp; the counselors, they were cool. Those two weeks each summer were a bubble that protected her and allowed her to be a kid. Since her parents died, she felt at times that walls would close in on her and that the change of scenery and routine that summer camp offers keeps them at bay. As she left each year she wondered when she would be back next and yearned for it. She also made up her mind that when she grew up she wanted to be a camp counselor, coolness included.…there was always that knock at the door of her heart ‘When can I go back to camp?'”

With this being the end of the 25th year of Comfort Zone Camp (first camp was in May 1999, at Camp Hanover in Virginia), I wanted to collect some stories of former campers and kids who found this amazing place later in life to convey their journey through grief and how Comfort Zone Camp helped them get through the storm. Working with Lynne, Krista Collopy, and other leaders at Comfort Zone Camp, we were able to have some former campers share with all of us their lives and how Lynne’s vision from her experience has, indeed, helped thousands of children heal, grow, and lead lives that honor their loved ones, and themselves.

I would like to introduce you to Niki Russo, Katie Pereira, Steve Roy, and Heidi Linck. After reflection and reading each of their stories, I thought it best to share their own words, unfiltered (rather than summarize), so we can all feel the pure emotion as they sort through it all. Having Comfort Zone Camp in their lives was a life changer for each of them, and having myself been witness as a big buddy for around 13 years now, my hope is that you will see from their eyes (and your own) why.

As you read each of these stories, there may be something relatable to your own. So, I encourage you, just as I did in reading each one, to open your heart and make it vulnerable.

The Reflection She Still Sees Each Day (by Niki Russo)

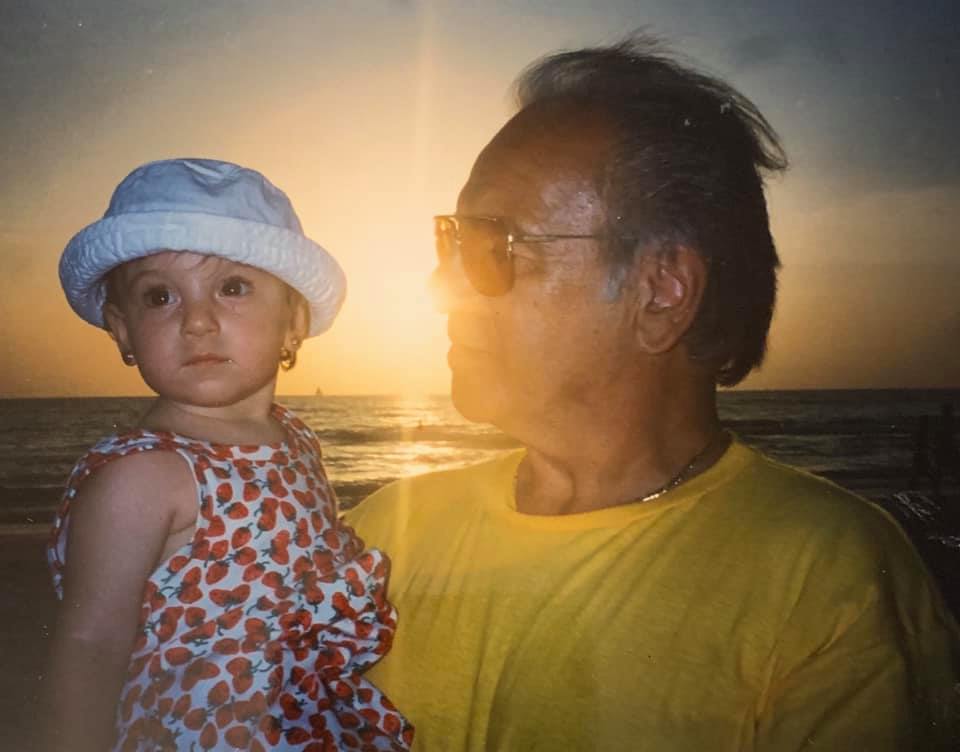

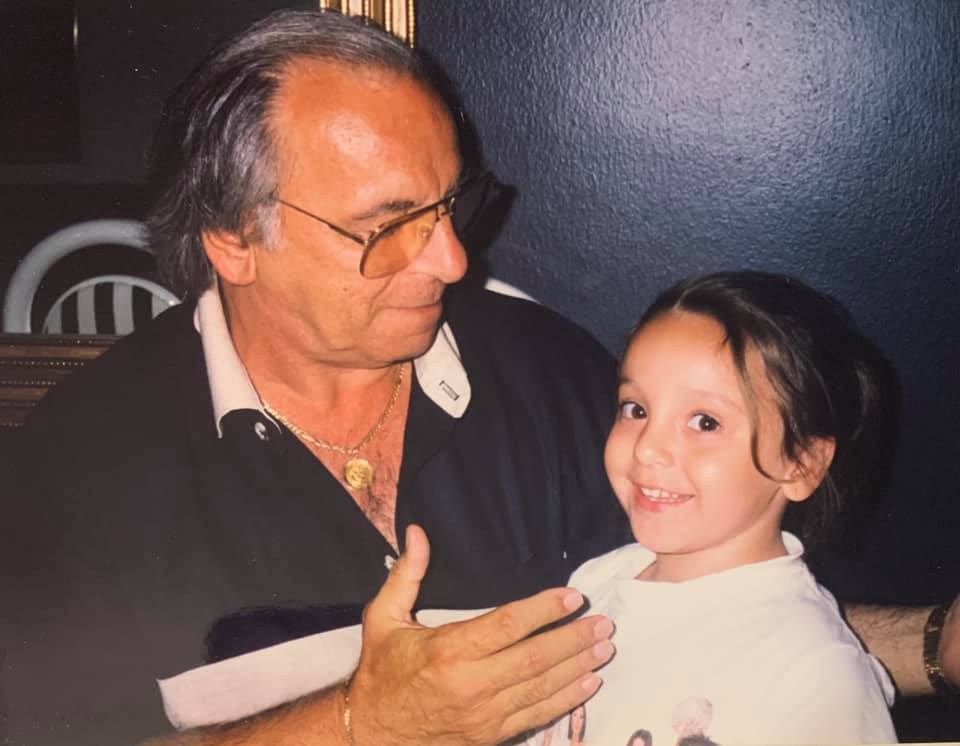

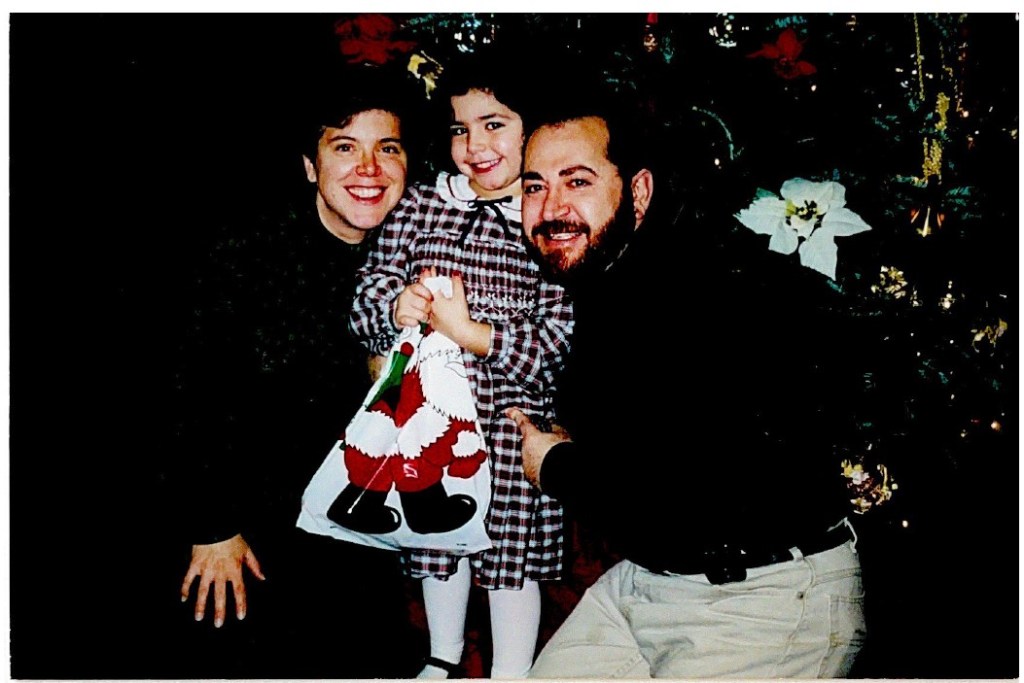

Joseph Russo had a gift for making everyone feel like family. His warmth radiated through every interaction, whether he was sharing a laugh or lending a helping hand. He possessed that rare ability to tease in a way that made you feel special rather than stung – a testament to the genuine love that powered his humor. When friends or family needed support, Joe was already at their door, expecting nothing in return. That was who he was to the world. But to me, he was everything: father, best friend, and the reflection I still see in the mirror nineteen years after his passing.

Being an older father came with its challenges. I struggled with others mistaking him for my grandfather, though I imagine those moments weighed even heavier on his heart. Looking back, I realize he worked to pack every minute of our eleven years together with meaning. Whether it was his vitality or my adoration that masked any limitations of age, I never saw him as anything but extraordinary.

His dedication manifested in countless ways. Beyond attending every game, he was my personal coach and fan club all in one – teaching me to dribble without looking, perfecting my baseball swing, and sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of college basketball. There was a major generational gap, but it didn’t stop him from believing his daughter could achieve anything. Showing his support for women’s sports, specifically the WNBA is something that I look back on and think fondly of.

In quiet moments, he showed me that strength included vulnerability, letting tears flow freely and never hesitating to express his pride or love. He also showed me what it looks like to love someone. The thought of his and my mother’s laughter from the living room while I fell asleep at night remains one of my most cherished memories, a sound I so deeply wish I could hear again.

There was something to be said about a man, often exhausted and unwell, who found endless energy for his daughter. The depth of love he poured into our brief time together explains why my grief remains infinite. Through actions rather than words, he taught me the meaning of unconditional love. It was simply his nature – the only way he knew how to care for those dearest to him, especially my mother and me.

The Last Memory and Holding on a Little Longer

They say cats have nine lives, and that’s how I explain my father’s story. It began in my fourth-grade year with what everyone thought was a simple cold. My mom initially brushed it off as typical “man flu” dramatics, but as days passed, it became clear something was seriously wrong. That “cold” turned out to be congestive heart failure – the first of many health battles my father would face.

Over the next two years, the hospital became our second home. Each new challenge seemed more daunting than the last: a defibrillator implant, an aneurysm, kidney failure leading to dialysis. Yet after each setback, my father would emerge stronger, more resilient, somehow managing to become an even better version of himself.

But like just cats, even my father’s remarkable resilience had its limits. Chronic leg pain from poor circulation had long troubled him, so he opted for surgery to find relief. The procedure itself was successful, though it ran longer than expected, leaving him more disoriented than usual. While I was accustomed to visiting him after surgeries, both he and my mom agreed this time was different – it wasn’t how they wanted me to see him.

On November 12th, the hospital called my mom about his dangerously high blood pressure, urging her to come immediately. When she arrived, he looked at her and said something chilling: “I am going to die today.” My mom did what she always did – reassured him, dispelled the darkness. Hours passed, his blood pressure normalized, and it seemed like just another false alarm in our familiar dance with danger.

After spending the entire day by his side, my mom needed coffee. He insisted she go, content watching sports on TV. She went downstairs, waiting for her cousin to arrive. In that brief moment of respite, the intercom echoed: “Code Blue MSICU.” Somehow, she knew. Minutes after she’d left his room, a massive heart attack took him from us.

People often ask if I regret not seeing him in those final days. I don’t. Instead, I’m grateful. My last memory of my father is pure joy – his excitement about feeling better, his laughter, his warm hug before I left for school. There’s a blessing in not witnessing the dimming of someone who always lit up every room he entered.

I feel the same way about my mom’s experience. While she saw him through his struggles, he waited until she stepped away before taking his final breath. Science might say we can’t choose when death comes, but in my heart, I believe he told his body, “Hold on just a little longer. I need more time with my girl before I go.”

Treating Grief like Milk with an Expiration Date

When someone tells you that after losing a loved one, the world keeps spinning, that everyone returns to their lives while you’re left alone with your grief – believe them. They’re telling you a painful truth.

Growing up, our world was perfectly contained: my dad, my mom, and me against everything else. In our story, we were the main characters, with others playing their supporting roles. Love seemed to overflow around us, with people always showing up to celebrations, filling our lives with joy.

Then my dad died, and it was as if everyone vanished with him. People kept their distance, as though our grief was contagious. Life continued, yes, but there was this unspoken expectation that my mom and I should just adapt, figure it out, move forward. Our family had always been uncomfortable with emotions, treating grief like milk with an expiration date stamped on the carton.

But how do you simply move on when half of your genetic blueprint has vanished? When your mother has lost her husband, her great love, her partner for all the days that should have stretched ahead of them? People understand missing those who are still alive, yet somehow death is supposed to make us stop missing them, stop loving them – or at least hide those feelings away, only to be examined in private moments when no one’s watching.

School was no different. Another girl in my grade had lost her father just a month before I lost mine. She carried her grief quietly, while mine spilled out loudly. Neither way was wrong, but my peers and even some teachers asked me to contain my pain, to make it smaller, more manageable for them. I couldn’t.

Even if I’d wanted to, even if I’d tried, my grief refused to be silenced.

Exactly Where You’re Meant to Be

Despite the challenges at school after losing my dad, some teachers became unexpected anchors. One day, my basketball coach Courtney invited her father to practice. When it ended, I saw my mom had come inside instead of waiting in the car as usual. My heart jumped – usually an unexpected appearance meant bad news. But something was different. She was talking with Courtney and her father Gerry, and there it was: a genuine smile. In those first few months after Dad’s death, so much remains a blur, but that smile shines through. It was the first time I’d seen real joy touch my mother’s face since we lost him.

Gerry shared that he volunteered at a place called Comfort Zone Camp, a place for kids who had lost loved ones. As they explained what the camp was about and asked if I wanted to go, I didn’t hesitate. Something inside me knew I needed to be there, but more than that, anything that could bring that light back to my mom’s eyes became instantly precious to me.

In the days before camp, I thought less about the grief work ahead and more about the freedom of being somewhere new. Here was a chance to just be myself, unburdened by others’ knowledge of my loss. I remember the drive there – perfect weather, endless possibilities ahead of me. When I walked into the dining hall with my mom to register, Kelly Hughes called out my name. For the first time in months, an adult looked at me and saw me – just Niki Russo – not the girl whose father had died.

They say major life events split our timelines: there’s who we are before and who we become after. For me, there were three versions: who I was before Dad died, who I was after, and who I became after finding Comfort Zone Camp.

Life offers rare moments when you step into a space and know, deep in your bones, that you’re exactly where you’re meant to be. That Friday at camp was one of those moments, and every camp weekend since has felt the same. After that first experience, I never looked back. I never will.

Being Her Truest Self

The greatest gift Comfort Zone Camp gave me was permission to grieve openly and honestly. After my dad died, some of my peers saw my loss as a weakness, turning it into ammunition to hurt me. Some even suggested that having me as a daughter had stripped my father’s will to live. They often mocked my deep connection to camp. Through my twenties, these dark memories would resurface often.

I used to harbor such hatred for those people, but time has brought two realizations: first, that while I remember myself one way, I might not have been at my best during those raw moments; and second, that perhaps they were wrestling with their own personal issues, lashing out as their only way to cope. I’ve found peace in forgiving them, and equally important, in forgiving myself.

A few years ago, a former classmate reached out with an apology for their past behavior, but they shared something that resonated deeply. They admired how, despite the torment, I remained authentically myself – continuing to grieve openly and returning to camp without shame. But this strength wasn’t mine alone; it was nurtured by camp. There, I found a space where I could be my truest self, not just in my grief, but in every aspect of who I was.

The unconditional acceptance I found there became my foundation.

I grieve out loud because Comfort Zone Camp taught me it was right and necessary to do so. I live each day, both inside and outside of camp, as my complete, unfiltered self. Camp’s most profound lesson was this: those who truly accept you – grief, joy, and everything in between – will never ask you to dim the very parts of yourself you’ve grown to love most.

The lessons from Comfort Zone Camp and a Truly Fulfilling Life

Lynne Hughes discovered something remarkable – a way to help us understand our grief more deeply in three days than we might in years of trying alone. Comfort Zone Camp doesn’t exist to “fix” grieving people, because we’re not broken. We’re simply humans experiencing the profound absence of someone who shaped our lives.

What makes Comfort Zone Camp extraordinary is how it showed me I wasn’t walking this path alone. It opened my eyes to a broader perspective, helping me recognize the depth of love surrounding me. This is a family that continuously opens its arms to newcomers with a simple, powerful message: “Share your grief with me. Tell me about yourself and the person you lost. Let me hold space for your story.”

Being part of Comfort Zone Camp has given me the gift of growing alongside my grief. Each camp weekend – and I’ll admit this selfishly – I leave transformed, understanding my grief better at this particular moment in my life. Finding camp when I did feels like an extraordinary stroke of fortune, because I know with absolute certainty that I wouldn’t be who I am without it. I once believed a fulfilling life was measured by just career and academic achievements, while very important to me still, Comfort Zone Camp also taught me a deeper truth: fulfillment comes from surrounding yourself with people who love you completely, believe in you unconditionally, and choose to walk beside you through every chapter.

This is how I’ve managed to grieve, heal, and grow throughout the years. My journey with grief will continue as long as I am walking this Earth, and I want to share it with people who want to be there for every step.

Because of Comfort Zone Camp, I know I’ll always have exactly that.

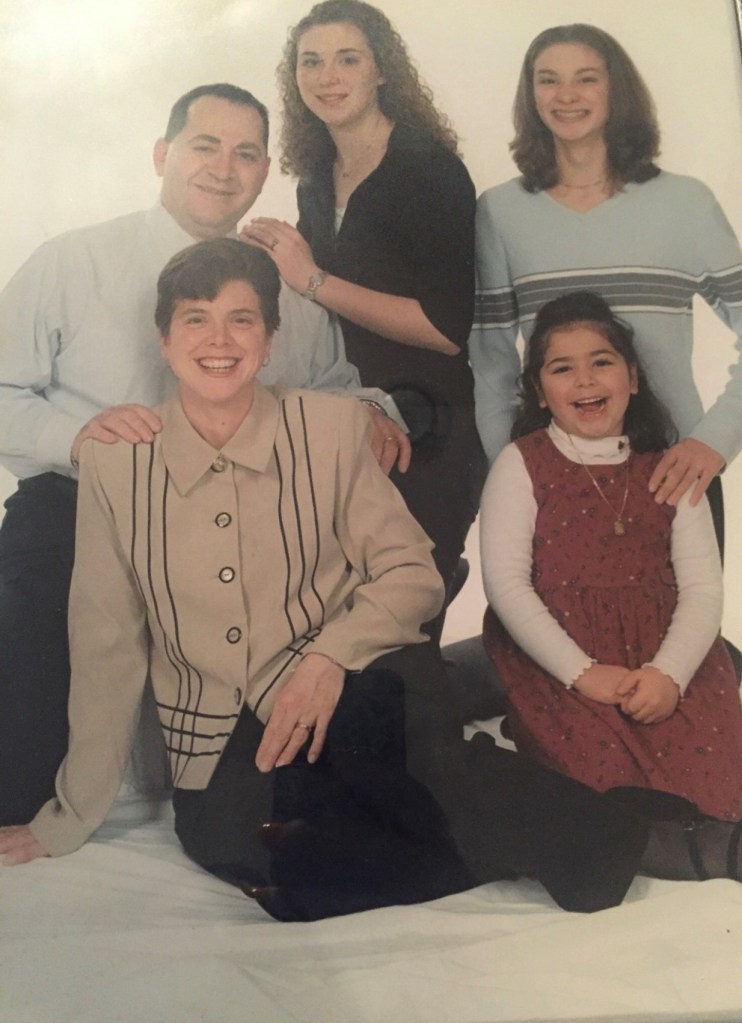

Anywhere Dad Was is Where I Wanted to Be (by Katie Pereira)

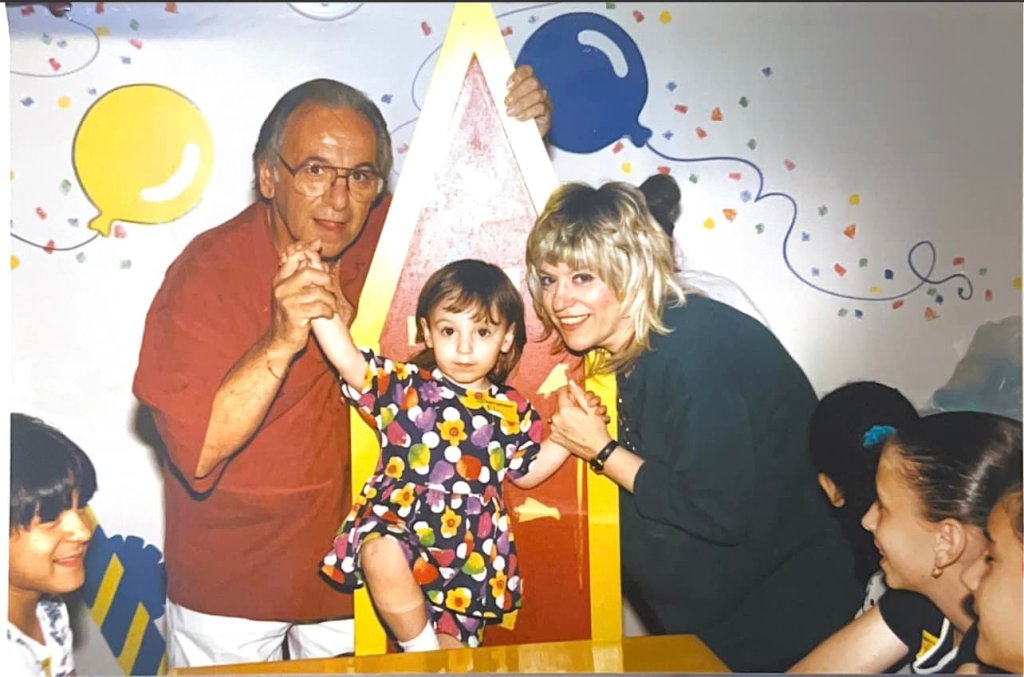

My dad Franco Lalama was a very kind and giving person. He often put everyone else before himself. My dad emigrated to the US when he was 7 years old from Italy. He was very proud to be an American, but the traditions from his Italian heritage and culture were of high importance to him. Those traditions were echoed in my day-to-day life and I still carry those out today. My dad was someone who truly loved what he did for work. He was a civil engineer for the Port Authority of NY & NJ. He is the manager for the structural integrity of the tunnels, terminals, and bridges. It is not lost on me that he was someone who valued integrity in his personal life and that played a huge role in his career and keeping others safe on their morning commutes and daily travel.

I always wanted to be with my dad, I was definitely a daddy’s girl. Some of my favorite times together were when I went to work with him. I was always so fascinated by his work and the hustle and bustle of the city. Anywhere my dad was, was where I wanted to be.

“Go Ahead, I’ll Follow”

My dad went to work one day and never came home. My dad’s office was on the 64th floor of the North Tower at the World Trade Center. His kindness and wanting to always help others were something he even did in his final moments of life. When the planes struck the twin towers on the beautiful morning of September 11, 2001, my dad made sure that all of his co-workers were cleared out of their office before leaving. He did not want to leave anyone behind. He is quoted by one of his colleagues who made it out that day with saying, “go ahead, I’ll follow”.

I remember going to school, I do not remember if I got to say goodbye to my dad that morning or not, but shortly into the school day my next door neighbor came to pick me up from school and bring me home, which I thought was strange. When I got to my house, I remember seeing our extended family and close friends and thinking why everyone is here in the middle of the week. It was not odd to have people at our home as we always welcomed people into our home for Sunday dinners or events on a regular basis. Walking through my front door I remember being shuffled to the playroom with my friends while all the adults congregated.

It has been almost 24 years since my dad died and everything now feels like a dream, questioning if things actually happened or if I am remembering them correctly. I do remember my mom not telling me right away that my dad died, but I don’t remember how long after the events had passed when she told me. When my mom told me about my dad, I was angry and sad and immediately wanted to shut out the world. I was confused and didn’t truly understand how my dad died or why this happened. I understood what death was at that age since I had other family members die before my dad, but the whole situation and complexity of the events of 9/11/01 confused me. I couldn’t understand why someone would do this.

Not Being Able to Feel How I Was Feeling, and Just Wanting to be a Kid

I grew up in a small town where everyone knew each other. I attended a catholic school in town where our family also attended church every Sunday. We were heavily involved with our church growing up. Mass every Sunday followed by Sunday dinners with my dad’s siblings and their families. I was in second grade when my dad died. I finished out the school year and then started at a new school the next year. I struggled academically before my dad died, but the being pulled in out of school that year had an impact on my academics even more.

I remember my friends in school didn’t know how to act around me, I immediately felt different and isolated from them, it wasn’t their fault, they were confused too. They didn’t understand how I could have a smile on my face or want to be a kid when my dad just died. Not being able to feel how I was feeling was very difficult and I felt this enormous pressure to always be angry and sad because it felt like that was what was expected of me. Deep down inside I just wanted to be able to be a kid and go about my days.

I have two older sisters, who both were in high school when our dad died. My family was a blended one. My mom was married before my dad and had my sisters, their birth dad was not a part of their lives actively after their divorce, my dad helped raise them and we were just one cohesive family unit, and I didn’t grow up thinking any differently. My dad loved my sisters so much, it didn’t matter that they were not his biologically. Since my sisters were older, they didn’t grieve alongside me or my mom, they spent a lot of time out of the house and with their friends.

My dad was one of seven children, and we spent a lot of time with his side of the family, Sunday dinners every week and spending time with my aunts, uncles and cousins was a part of life very frequently. One of my dad’s siblings lived in the same town as us. I went to school with my cousin who was the same age as me. My mom was a stay-at-home mom with me and she would watch my cousin alongside me, so we grew up together and spent a lot of time with each other. After my dad died it wasn’t too long after that most of his siblings turned on us, and disassociated themselves from my mom, sisters and me. My mom made every effort to still get me to be able to with them, even though they treated her so poorly after my dad died.

Unfortunately, death can bring out the worst in people. My dad was the glue that kept everyone together, and once he was gone it was like his siblings didn’t see a reason to be a part of our lives anymore. I didn’t get to see my cousins as often. What went from weekly visits, turned into months, then once a year, then nothing. This was another loss that had me confused growing up, thinking that I wasn’t enough for people, like I did something wrong.

Finally, Feeling Understood and Knowing I’m Not Alone

My mom read an article in the newspaper about Comfort Zone Camp. They were doing one day programs for kids and their families. I attended two of these before going to my first weekend camp in April of 2002. I don’t remember how I felt about going to camp, but what I do remember is how at ease and at home I felt. I finally felt understood by those around me.

Comfort Zone Camp truly showed me that I was not alone and there was no right or wrong to way to feel while you were grieving. It is the place where I don’t feel like the girl with the dead dad. I feel complete. I am forever and deeply thankful for having Comfort Zone Camp in my life.

So, take a chance and go. Comfort Zone Camp was the support system I didn’t know I needed until I experienced it for myself.

Not Having to be Anyone Else Other Than Myself

People often have a confused look on their faces when I mention Comfort Zone Camp with pure joy. They visibly look uncomfortable and ask questions about what that is like, how can you have fun there, etc. They would also ask me what I loved most about Comfort Zone Camp and that is how it was the one place where I wasn’t defined only by my loss, they didn’t just look at me and say you’re the girl whose dad died on 9/11. It was in my first moments at camp where I truly did not have be anyone else but myself. Feel how I wanted to feel. If I was happy, I could be happy and if I was sad, I could be sad, but the best part was that I wasn’t judged for how I was feeling after my dad died.

Note: Katie now pays it forward serving as the Regional Camp Director for Comfort Zone Camp

Boy Scouts, Bunk Bed Brothers, Star Wars, Hanging onto Dad, and The Solid Dark Line (by Steve Roy)

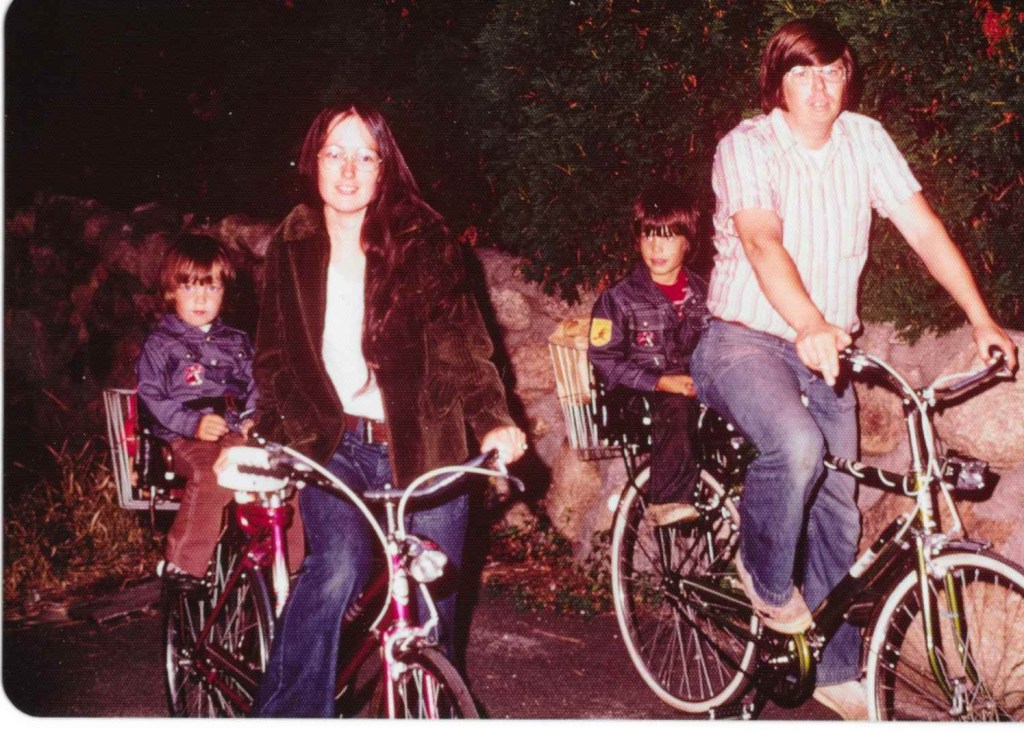

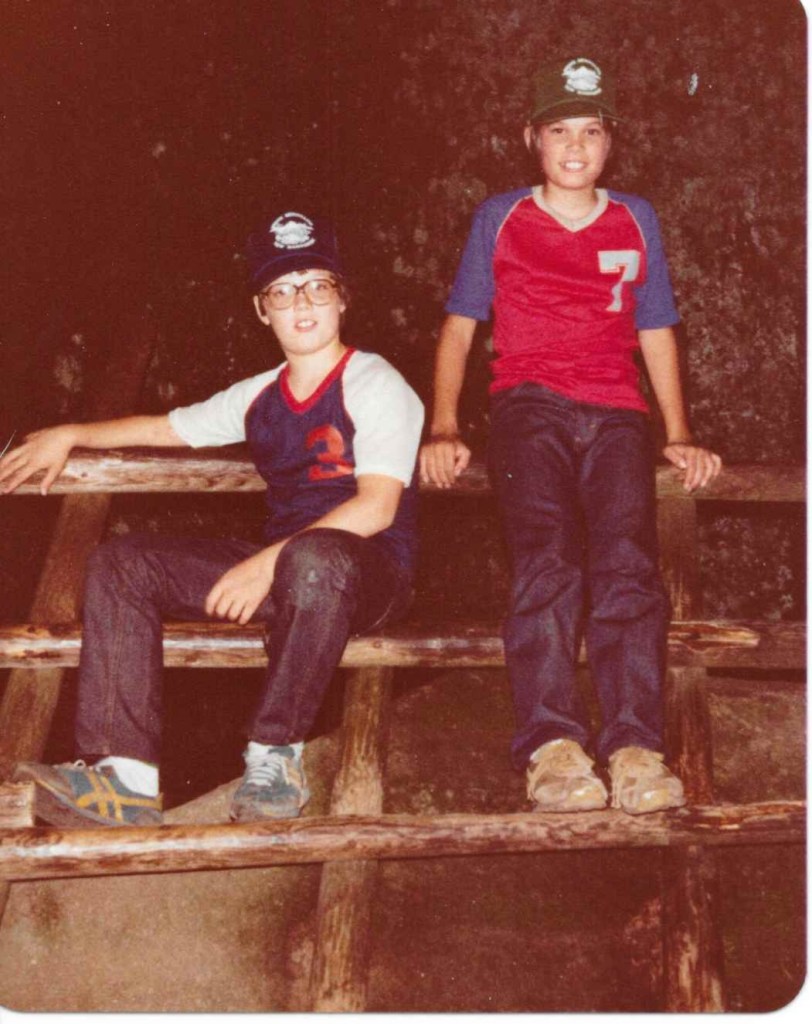

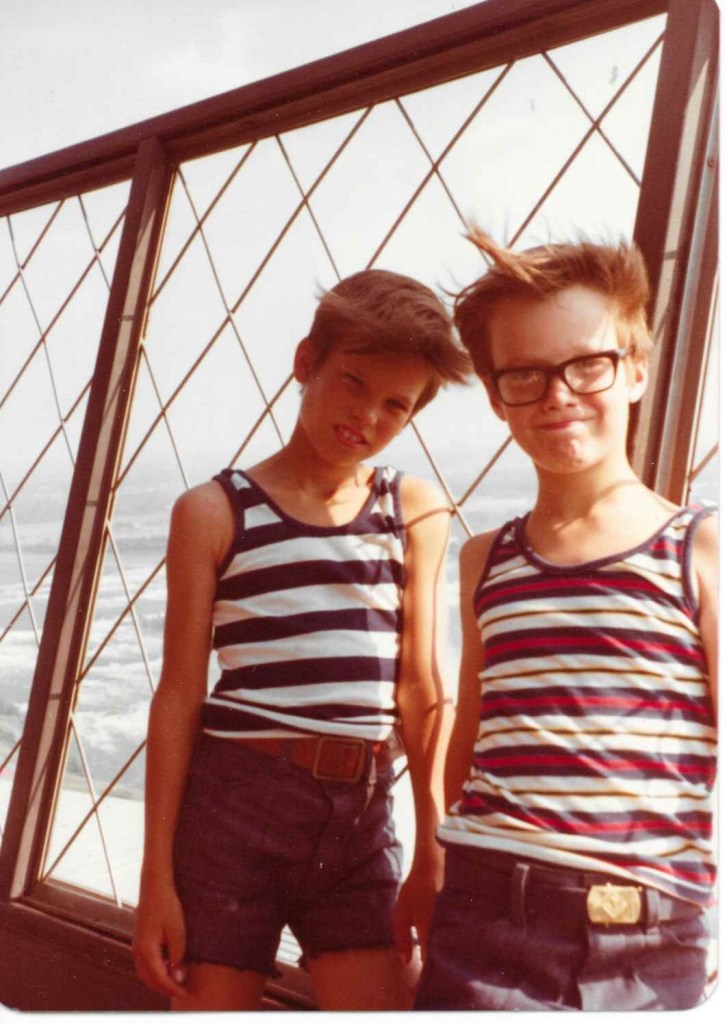

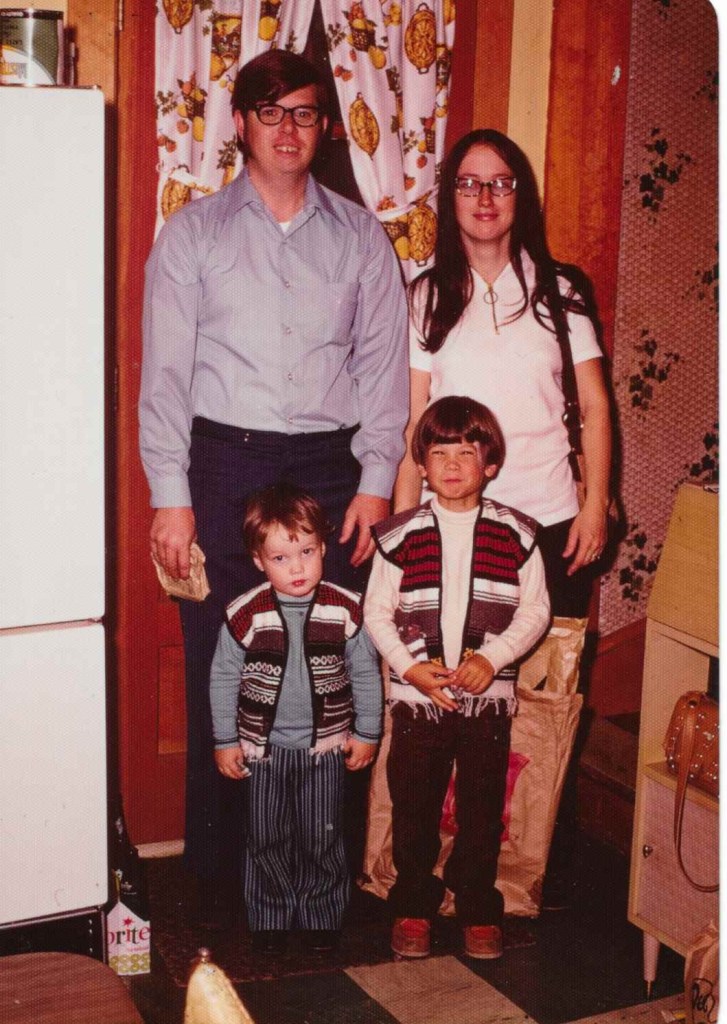

On April 6th, 1981, I was 11 years old. My older brother, David, was 13 years old. We were both Boy Scouts with Troop 4, Clinton, Massachusetts. Clinton was about a half an hour away from where we lived in Fitchburg. On Monday nights, our dad would drive us to our Boy Scout meetings in Clinton. He’d take us in his big white Chevy van, my brother and I taking turns sitting in the passenger seat, the other sitting on a makeshift seat in between.

On our drive to the meeting that night, we were hit head-on by a drunk driver. He was driving at speeds over 90 mph while on the wrong side of the road. I was the only survivor of the accident – or The Accident, as it became known.

My Dad’s name is Larry – he was 36 years old when he died. My memories of him are limited – though pictures do bring stories back to me. There is a solid dark line separating my Before and After, and I think that has a lot to do with my limited memories. I have always felt that the physical trauma of the accident created a block in my mind, making it difficult to hop back into the ‘Before’. I was conscious when the EMTs found me on the road – all three of us had been ejected from the van.

I was screaming for my mother, while trying to stand on two badly broken legs, a broken arm and many other injuries. I don’t recall the accident happening, being in the road, screaming etc. – but a witness on scene (he’d been following us) and the EMTs all reported that I was awake and conscious through it all. I believe the brain protects us from trauma when it can – and none of those accident-specific memories have ever come back. So, I think that has something to do with how hard it is for me to remember much from before the accident.

But some things remain.

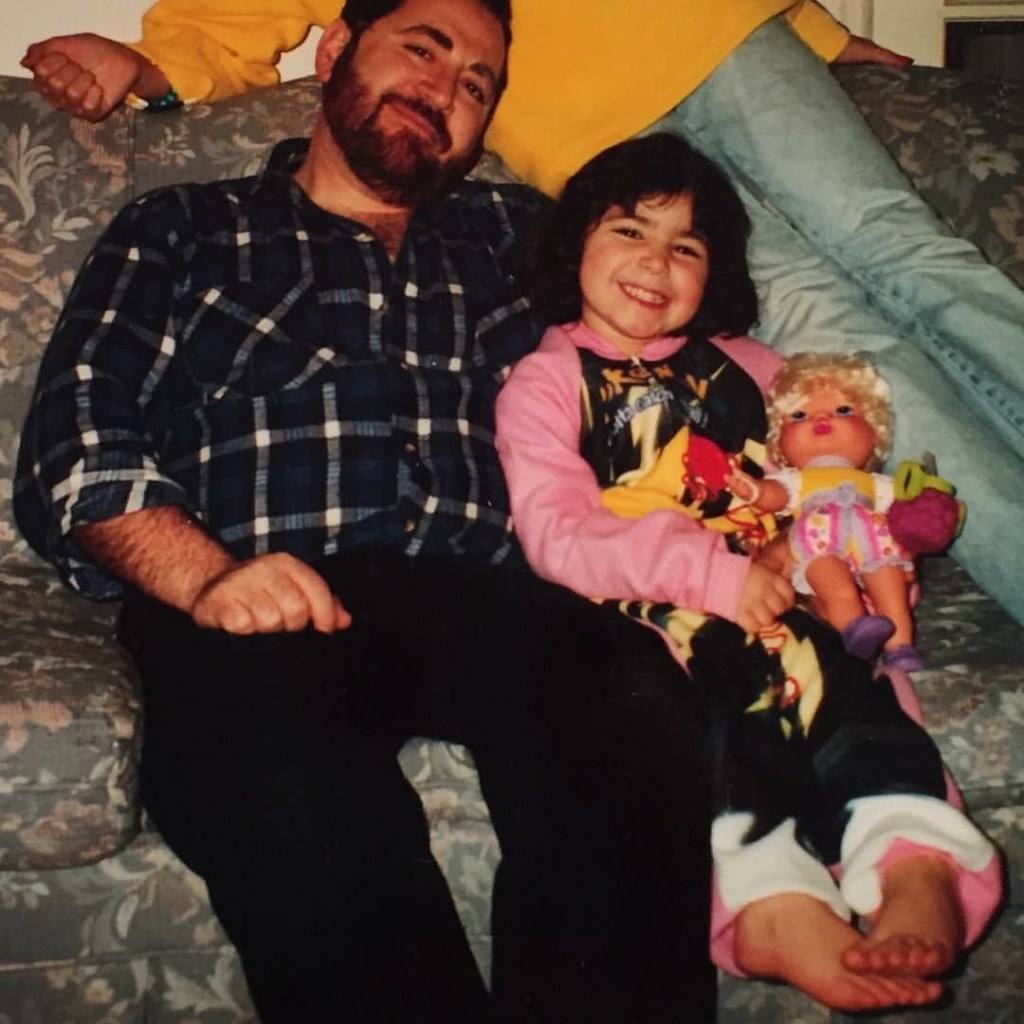

My Dad – he was awesome. He was Cubmaster of our Cub Scout pack (before we moved onto Boy Scouts). He volunteered his time, and I remember always being so proud of the fact that MY dad was in charge. I just felt bigger, taller. He was very generous with us.

We were quite poor, living in a first-floor tenement apartment, but he and my mom always found ways for us to have great Christmases. He had a big reddish-brown beard and a belly – and I loved the fact that we both had similar builds. As a kid, I remember sticking out my belly and pretending to be him. My dad was a bowhunter – he never got a deer, but he loved the hunt. We had hay bales set up in the back woods and targets set up on them. He taught us how to shoot with a bow and arrow. I remember never being able to pull back his compound bow and marveling at how very strong he was. My brother and I would use regular bows.

Though he died when I was eleven, he was able to instill some great values in me I believe. He taught me to respect our elders – I once made a smart-aleck comment when my great-grandmother had given me and my brother each a quarter, and my dad made sure I understood that it wasn’t right and to speak to her with respect. He also told me to never hit a girl – which is obvious, of course. A friend and I were squaring up for a fight (over something dumb), and my dad saw it and immediately pulled me away. My friend and I were both ten years old, but she was a girl and he wouldn’t have it, even if we were just kids. I will never forget that.

And his generosity – of his time and attention – is something I believe he gave to me. Or at least showed me that that was the right way to be.

My favorite memory of my dad has to be the time when he took me on the back of his motorcycle, and we rode to a friend’s place for a haircut. Big hills, going fast, hanging on to him as we zipped around corners – feeling so scared, but so excited and safe at the same time – hanging on to him, my hands barely clasped around his waist.

I miss him.

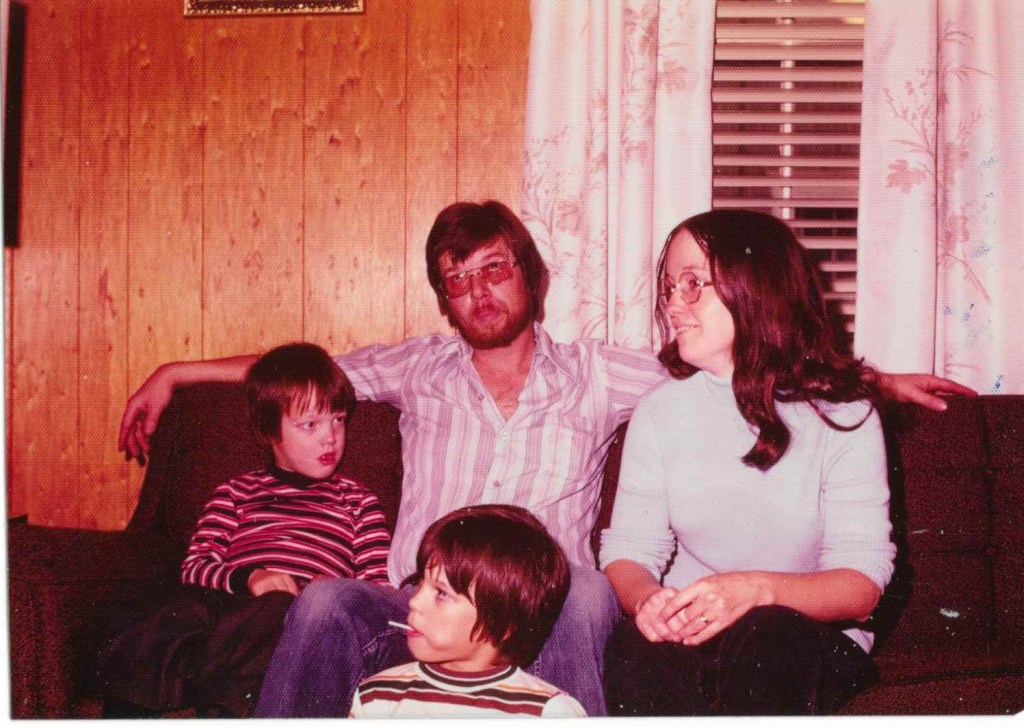

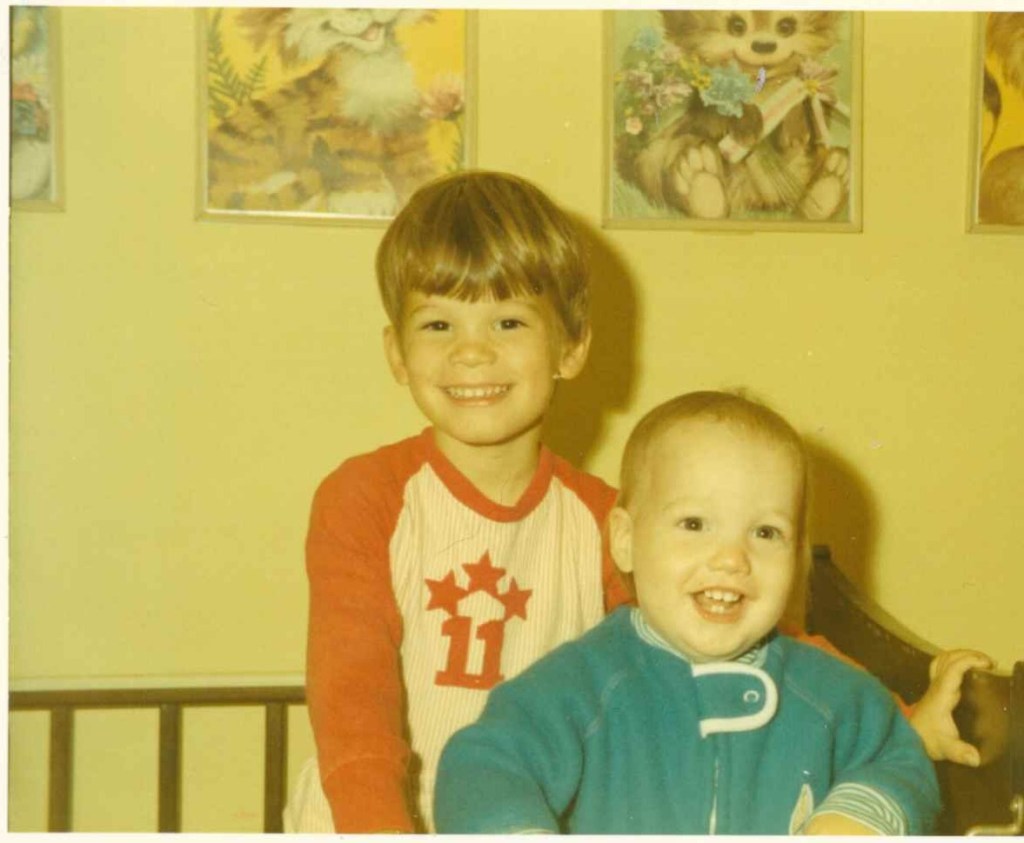

My brother’s name is David – he was 13 years old when he died. As I said, my memories are limited in the before. So much of what I ‘remember’ is based on pictures – and stories of others. But there are things about David I’ll never forget.

We shared a bedroom – bunkbeds. He was always up top, and I’d kick from underneath trying to push his mattress up. He’d ball up socks and throw them down at me. Almost two and a half years younger than him, I played the role of instigating little brother well. I annoyed him, he’d fight back and get in trouble. That sort of thing. David hung around with the older kids most of the time.

Our age gap would not be a big deal as adults – but as kids it’s a completely separate social situation. David was artistic and creative – he loved to draw and make models. He was a smart kid who got bored in school – he did the bare minimum when he got bored, and his grades reflected that. He could learn quickly and was almost immediately good at everything.

An example – in the late 70s, Atari came out. My uncle had it and all of his friends at the time were probably a good 10-15 years older than David. They were playing the game Breakout and were just unable to get very far. Finally, David asked if he could try, and within moments that ball was breaking through to the top of the wall and the points skyrocketed. He just had a knack for things. I see that trait in my youngest son, Joe.

So, while David normally hung around with older kids – and while we fought a lot, we did have our things that connected us. The main one was Star Wars. We both fell in love with that world and pined for every action figure and ship we could get. But being poor, it was hard to get a lot of that stuff outside of birthdays and Christmas. But we eventually had quite a collection. We’d play ‘Star Wars,’ choosing action figures and battling. He always chose first and always picked Han Solo. I loved those times with him – the age gap melting away as we created our own galaxy, far, far away.

My favorite memory with David is easy. It was 1980 and The Empire Strikes Back had come out. We, of course, loved it. At some point we learned that the Yoda action figure was being released. We had saved enough birthday money to get one. It was a Saturday morning, and Child World (huge toy store back in the day) was supposed to be getting the figures in – so David and I walked what seemed like a really long way down to John Fitch Highway in Fitchburg to Child World. In actuality it was only about two miles. But I was 10 or 11 at the time, so it seemed far.

We talked on the walk – about Star Wars obviously, but also about other things. My dad had moved out a year or so before that – our parents were separated – and I do remember asking David if he thought he would move back in. He didn’t know. It was odd for us – our dad came over just about every night, so it didn’t feel very different to us, but we also knew he left every night too. We touched on that stuff and probably other things – but our focus was Jedi Master Yoda. We got to Child World, waited for them to open, and then ran to the action figure aisle – only to find that they didn’t have any Yoda figures. Disappointed, we left.

David took us across the street to Burger King. That was something we just didn’t do back then. I don’t remember if they had breakfast back then or if we waited for lunch – that detail is gone. But the memory of that day with David – on what felt like a journey to a distant land, both brimming with shared excitement for something we both loved – is something I haven’t forgotten.

And not getting Yoda that day might have been a good thing. We had more real time together – no distractions that a new toy might bring. We eventually got our Yoda action figure and, for a while anyway, David chose him first.

A Journal Found, Raw Emotions, Words Spoken and Not

My mom died 25 years ago (in 2000), at 54, nineteen years after the accident. Cleaning out her house I found lots of things – one being a journal she kept that documented the day of the accident and the months that followed. So, I am in the unique position of having my own thoughts of that day – and her real-time adult emotions and chronicling of that day and its aftermath.

My memories and her journal line up in regard to the basic facts. David and I had been fighting. I was instigating again, and David was having a hard time getting the brunt of punishments for retaliating. He was being put in a no-win situation – take my ribbing…or retaliate and get in trouble. The fight was bad, and I refused to go to the Scout meeting. My Dad arrived and we were both told to get in the van. I could quit at the end of the year if I wanted to but needed to see it through. From my mom’s journal I learned their side of things – my dad saying he didn’t know what he was doing, how to be a dad and all that; my mom telling him we all do the best we can; their “I love you” to each other and the promise to figure out how to handle the problems with the boys.

We left for the meeting and were lectured about getting along, not fighting and all that. And how we’d both appreciate having each other as brothers as we got older.

I remember leaning my head against the passenger window for the rest of the trip. There was silence in the van. We were all angry with each other; frustrated.

I have a quick flash memory of being lifted onto a gurney of some kind. That’s the only accident-related memory I have – as I was likely being moved from an ambulance to a hospital gurney of some kind – not sure.

My emotions were anger and frustration – but not regarding their deaths. I wasn’t awake and didn’t know that they died until after their funerals etc. I was in and out of many surgeries and not conscious for any of that.

I believe I had figured out that they had died before being told, though. But the few times I woke up, I saw my mom sitting there; blurry as my glasses had been broken in the accident. She never visited anyone else, and no one else was with her. I couldn’t speak as I had a tracheotomy… but I remember mouthing the words to her – “Where’s Dad? Where’s David?”

She leaned forward in her chair, and I could see her face a bit better. She started with, “It was a very bad accident…”

I turned my head and looked away as she told me the words I didn’t need to hear in order to know. I shut down, didn’t cry.

From Four to Two, New Town, New Home, New School, and Wanting the People I Knew

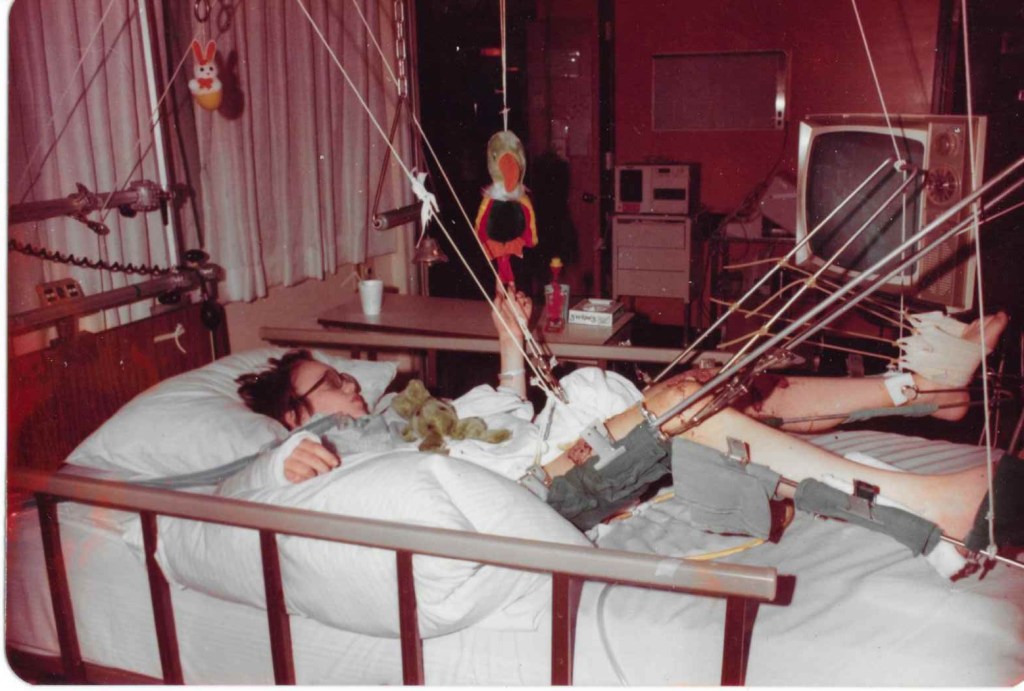

We went from a family of four to a family of two. Things were obviously very different. I was in the hospital for six weeks – mostly in traction. My 6th grade class came for a field trip to visit me. Once out of traction I was put in a body cast. I was able to come home to recover at home in the body cast. After that, I was back in the hospital for another six weeks – learning to walk again.

When I came home for good, it was strange. The bunk beds remained but the room was now mine. Mom and I moved an hour and a half away in the summer of 1982. New town, big house (insurance money) – but no dad, and no brother. New school. None of my neighborhood friends around anymore – that protective circle gone. I had bright scars covering my legs, head and stomach.

We moved to a small town with a class of 80-something kids who all grew up together. I didn’t have much of a chance.

Even before moving, I skipped a lot of school. Once we moved, it was even worse. I had no interest in this new life I had been given. I didn’t ask for these changes and I craved control. A low point that first year in our new town involved the principal in my bedroom trying to force me to go to school – and my eventual ride in the back of the truant officer’s police car bringing me to school.

I especially struggled around the month of the accident – report cards show this as well – as A’s and B’s turned to D’s and F’s . My mom and I went through our ups and downs – and I do remember believing very strongly that she would have preferred it if David had lived, and I had died.

My mom wanted me to continue with Scouting – to earn Eagle Scout in honor of my dad and brother. I liked the sound of that idea, but didn’t like the pressure and was not emotionally ready to do it. I made it to Life Scout and had to stop. I didn’t want to do it without them.

As I grew older, I understood why my mom needed us to move – too much of David was in our old place and she just could not handle that. Our place in Fitchburg was for a different family – this new family – me and her – needed to start over somewhere new.

While I understood that later, it was never what I needed. I needed my friends – the people who knew my dad and who knew David…the people who went through this loss with me. None of that could be found in our new town.

In 2011, a Random Email at Work

I learned about Comfort Zone Camp through an email at work. I clicked the link, found the website, watched the video and was drawn in immediately. A training was not too far away from me, so I went and have been involved ever since.

As a natural introvert it went against everything I knew, sign up for something and to go to a place alone and put myself out there like I did. But the pull was too great. I figured I was beyond my own grief (very wrong about that) but could help others with my experience (very right about that).

Writing TO Dad, David, and Mom, and then my life changed

When I went to my first camp it had been thirty-one years since my dad and brother died – and almost twelve years since my mom had died. I thought I had moved beyond my own grief. When I was handed an index card for bonfire at my first camp and learned that I, too, could write a note to put in the fire my life changed. Not an exaggeration. I had written about them so many times – but I had never written TO them.

That first bonfire note allowed a conversation with them to begin again – and that conversation has continued ever since. Notes to them have gone into sixty or so bonfires by now and they are an active part of my life – their story, my story, and what can be learned from them all came about when I was handed that first index card.

Grief is Unique as a Fingerprint; Comfort Zone Camp Understands This and You

I would want to tell people experiencing something similar to give Comfort Zone Camp a chance. To allow yourself to be open and vulnerable and to trust in the knowledge that while there isn’t a single person on earth who has experienced what you are experiencing; you are not alone.

Grief is as unique as a fingerprint, as are our relationships with the people in our lives – those we’ve lost and haven’t lost. And because our relationships are different, unique, so is the grief we feel. So even if two siblings both lost their mom, their grief experiences are not the same, because the relationship wasn’t the same. Comfort Zone Camp understands this.

The environment is friendly, caring, supportive and, perhaps most importantly, pressure-free. If you want to tell your story you can; if you don’t want to say a word, then don’t. I know that I would have fought tooth and nail not to go to Comfort Zone Camp if it existed back in the early 1980s. I know how stubborn and closed off I was. But I also know that I would have benefited greatly from going as a child – because I have benefited greatly as an adult – and the focus isn’t on the adults. So, imagine what twelve-or thirteen-year-old me would have gained from time at Comfort Zone Camp.

There have been times at camp where the other Big and Little Buddies have made me feel like a little buddy – or at least supported like one. The community we build in each healing circle is my favorite part of camp. It lifts us all up – Healing Circle Leaders, Big Buddies, Little Buddies – all of us.

And it’s wonderful.

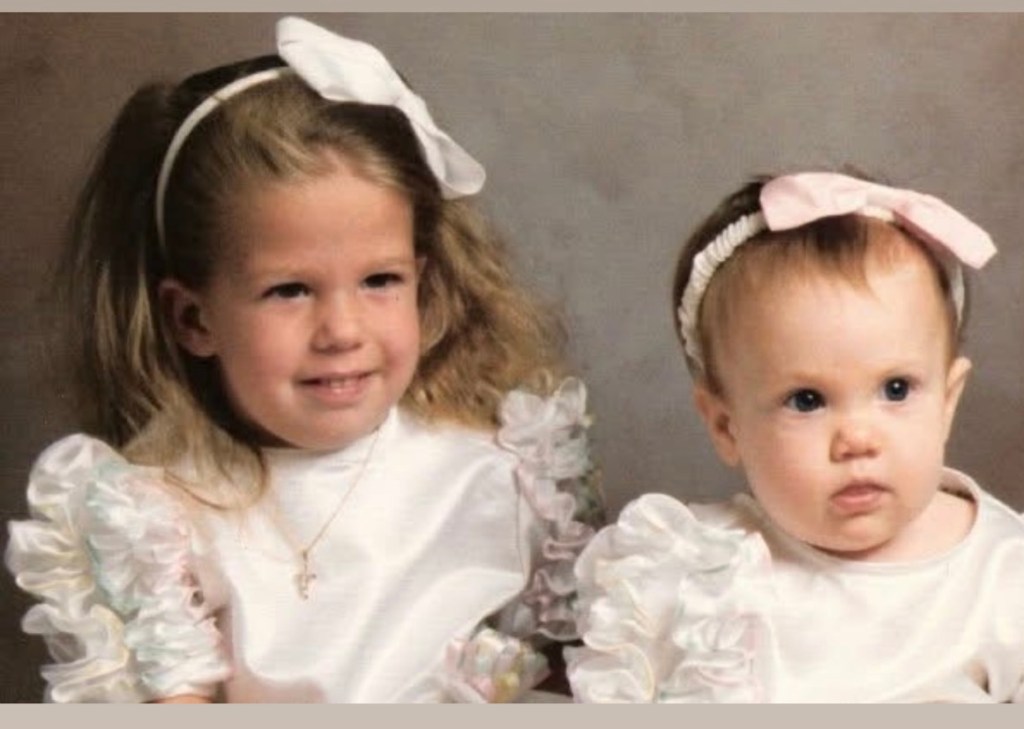

A Childhood Lost and Notes to Heaven (by Heidi Linck)

When I was five years old I lost my little sister, Shaina. She was only three years old. Unfortunately, I do not have many memories of her. I do know that she was a spunky little thing, and I was a little bit afraid of her! We shared a room. When it was time to clean our room, our mom would sweep everything into a pile and split it in half, so we were each responsible for one half. One day I remember working so hard to clean up and looking over to see Shaina taking a nap. That’s a day we all still laugh about.

The day it happened I did not feel well. I just wanted to stay on the couch and watch tv. Shaina wanted me to go outside and play but I said no. So, she went out to play by herself. My mom was in the kitchen with the back door open to keep an ear and eye out for Shaina while she was outside.

We had a pool in our backyard, but Shaina and I hated it and never went near it. But that day, something happened and she did. She went too close and ended up at the bottom of the pool. No one heard a splash, a scream, nothing. My older sister, Jessica, who was twelve at the time went outside to check on Shaina and saw her at the bottom of the pool. She jumped in immediately to get her, but it was too late.

I remember hearing my mom scream. I ran to the back where I saw her holding my lifeless sister. I don’t think I knew at the time exactly what I was looking at, but I knew not to interrupt. I pretended I saw nothing and I went back into the other room. The fire department was the first to respond and I remember them working on Shaina on the front porch. That’s the last thing I remember.

I know that she went to the hospital with my parents, and I know that while they were there they saw my sister Jessica on the news being interviewed without their knowledge or permission. I know that the doctors got her to a point where a machine could keep her alive but that she would never really live again. She never woke up and my parents had to make the decision to take her off of the machines.

I went to a family friend’s house. I remember drawing pictures for Shaina for when she came home. I didn’t know that she would never come home.

Trying to Pretend It Never Happened

The day I lost my sister I also lost so much of my childhood. At her funeral I remember not crying. I just tried to make everyone else happy. I was already trying to pretend it never happened. I did cry when we buried her, and I remember crying one time in my room because it was so weird sleeping in there without her.

I honestly don’t think I cried again or mentioned her name for years. I never wanted to be the reason someone was upset. I never said her name because I didn’t want to remind my parents. Of course they never forgot, not for a second, but I was so young I didn’t realize that.

One day we were at a birthday party and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, but I saw a rainbow. I told my parents that I thought that it was Shaina’s job in Heaven, to paint the rainbows. We would go to her grave sometimes, which I liked except for the fact that my parents would get upset. I really felt like it was my job to keep everyone happy.

Have You Lost Your Mind, Mom??!!

I went to the second ever camp – Camp Comfort as it was at the time. My mom worked at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Virginia (she went into nursing after Shaina died) and someone told her about the camp. I want to say I was nine or ten. I thought my mom had lost her mind. A camp to talk about my dead sister!? Why on earth would I want to do that? I did not want to go at all, not one bit.

Thank God I went.

I never talked about what happened, or what I had seen that day. I never wanted my mom to know that I saw her holding Shaina, that I had seen something so awful at such a young age. I told my healing circle things that I had told absolutely no one. I learned that it was ok to be upset, and it was ok to let other people be upset, and it was ok to talk about Shaina. Lynne and Kelly Hughes were such angels. I haven’t seen them in years, but I still hold such a special place in my heart for them. My first Big Buddy’s name was Gwen, she was wonderful. I just remember feeling so heard and so supported.

I wrote Shaina a letter and put it in the bon fire, we wrote notes and let them float to Heaven. I just felt so connected to her and that I may actually start healing.

Don’t Have the Words for Comfort Zone Camp, other than It Saved Me

I was lucky enough to go back to camp a number of times. I was able to open up more and more each time. Then when I was in high school my dad was diagnosed with cancer, and he had a really hard fight– that he won!

But while he was sick I was able to go back and the community was so wonderful, there were lots of campers that I knew and some who had lost a parent to cancer. I was so afraid of losing my dad that I was grieving him while he was still alive. To have an outlet to share my fears and be around people who knew the feeling because some had lost a parent to cancer was just so good for me. No one made me feel crazy or dramatic- they just listened.

I don’t really feel like I have the words to explain what exactly CZC did for me except maybe- it saved me. I didn’t realize how much I was holding inside.

I feel like maybe because of how old I was when Shaina died her death got harder for me the older I got. Even today I sob just writing all of this out. But before Comfort Zone I wouldn’t have ever let any of these words come out. I was able to open up to my family, we started talking about her more, and I started sharing more about how I had been affected.

For others considering Comfort Zone Camp, I would say “what are you waiting for?”

I get it, a bereavement camp does not sound like a great time but that’s only a small part; you don’t have to talk about anything, you can just listen. Comfort Zone Camp is there to be what you need; it’s a community where you can express yourself if you want to or you can just be there to soak it in.

Comfort Zone Camp truly does show you that you are not alone.

Where the Light Meets the Sea

One of the sacred parts of the weekend is the Saturday bonfire, it is different at each camp. However all hearts are warmed by the presence of each other and the fire that sends notes to loved ones above.

It usually concludes with a song from Brett Eldredge (‘Where the Light Meets the Sea’) which conveys a message of longing, hope, and finding peace while acknowledging the pain of separation and difficulty letting go when you didn’t want to and capturing the universal desire for belonging and purpose. It also conveys a place that serves as a sanctuary where a child can find solace, peace, and tranquility to heal, and be a respite from life’s challenges and heartaches. It’s a gentle reminder of the strength it takes to let go and find peace in the face of heartbreak and that sometimes, leaving is the only way to create the space needed for personal growth and healing.

I asked Katie Pereira to record one for this 25th Anniversary article so others can have a view into part of the experience, and I would like to invite you all to join as it concludes by watching the video below (around 6 minutes, from Camp Hanover in November 2024 – where the very first Comfort Zone Camp was held in May, 1999):

Does my Big Buddy still go to Camp and Big Buddy Buddies

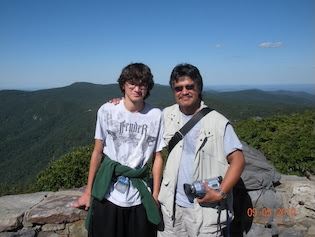

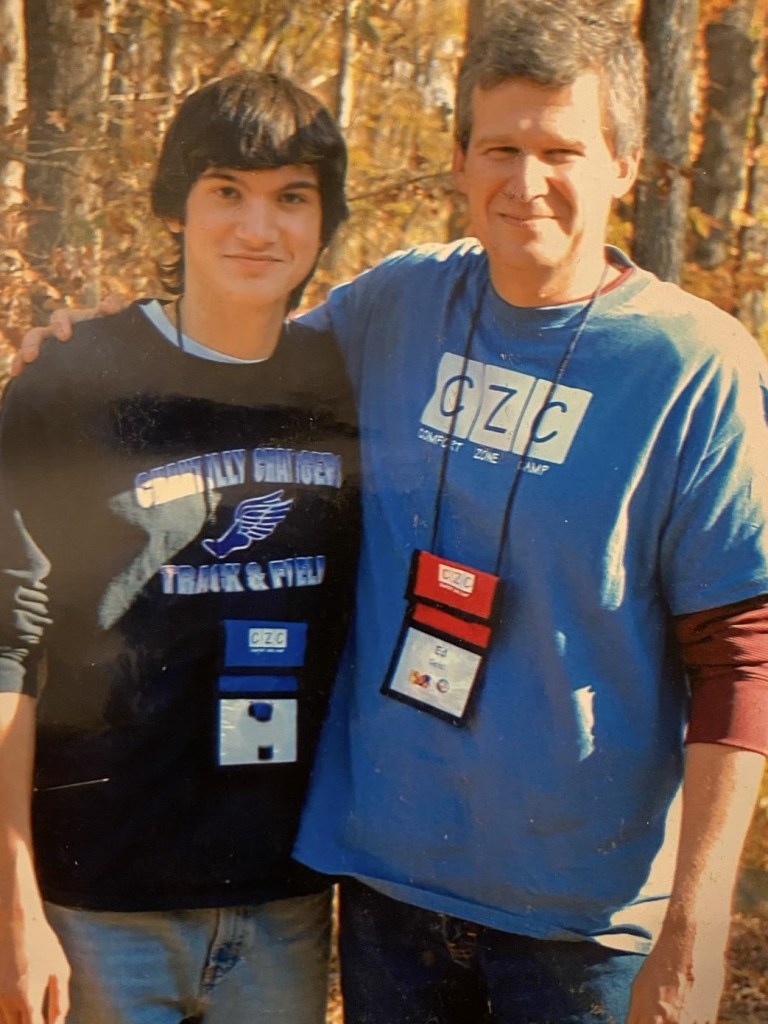

Does my big buddy still do camps? Yes, he does Zarek!

When I was at a Camp in Williamsburg in April 2024 I ran into Lynne and she mentioned to me that one of my former little buddies, Zarek, asked about me. We were at camp in June 2012 after he had recently lost his dad, and he is involved in Comfort Zone Camp now as a big buddy in the Northeast. It was great to hear he is doing well and warmed my heart to know that the weekend we had was something that he treasures.

Zarek was just sixteen when his world was shattered; his sister threw his bedroom door open saying she could not wake up their dad. His father, a joyful, music-loving man who played saxophone and yes, even bagpipes, was suddenly gone. Today, Zarek is one of the most passionate Comfort Zone Camp supporters, a little buddy and camper turned Big Buddy volunteer, helping others heal as he did. He also ran the recent NYC Half Marathon on behalf of Comfort Zone Camp. When we met 13 years ago, he was a grieving teenager who was “very hesitant” to attend Comfort Zone Camp.

Here is what he had to say in a recent Comfort Zone Camp Grief Relief 5K Newsletter:

“After some initial awkwardness, my assigned Big Buddy and I clicked, and he ended up being a great friend throughout the weekend, supporting me, even if that was just listening and being there.

The other campers and I got along very well, and we helped bring each other out of our shells. The whole weekend ended up being a blast, learning comforting ways to grieve and heal.

CZC turned out to be one of my favorite life experiences.”

I hope you are reading this Zarek and want to say how proud I am of you and what an honor to be your big buddy that weekend. I know that you are now a thriving adult who will always keep the memory of your dad close, and an incredible big buddy for others that are trying to sort through it all.

What I have also come to appreciate as a big buddy are the friendships made through the years, knowing that we can all lean on each other and have this common bond knowing that there are times in life where sharing our vulnerabilities can strengthen our humanity. I have experienced through my own life, and spending time with others that with every wound encountered in life, there is a scar, and with every scar there is a story. When you realize the strength of your scars, there is a story behind it that others can learn from, such as the opportunity for a conversation with fellow big buddy Anthony Jackson who reminded me that the colors we see can blind ourselves.

Being part of Comfort Zone Camp has been one of the most transformative times of my life, and truly understanding and relating to others from all walks of life and who have experienced an unimaginable loss helps me walk in others shoes and see through other eyes. Camp weekends have it all…compassion, understanding, perspective, sadness, hope, joy, perseverance, resilience, adaptability, and the absolute best in humanity.

I am moved every time I go, and I sure don’t like going when it’s time to leave camp.

So, when can I go back to camp?

Soon, very soon.

Truly Living

At the end of each camp there is a Memorial Service to honor the loved ones of the little buddies at camp. Many campers will act out something (throw a ball, go fishing, etc.) with their big buddy that reminds them of times with their parent/sibling/loved one that they lost, or play a song that they loved and brings back memories of them. At the end of the service we will all gather in a circle, families included, and arm in arm swing to ‘Lean on Me’. There is usually not a dry eye around during the service.

At my most recent camp, a little buddy remembered his parent by reminding us all to be truly living.

I thought about it when I left. Over the years I have written about how vulnerability and sharing it with others can be seen as a weakness, however it can be how strength is discovered and serves to encourage others you don’t even know, that they are not alone. I have wrestled with expressing my vulnerability in writing a letter to my home of nineteen years and saying goodbye. That was difficult.

More recently, and after my most recent camp, I opened and read through a letter I wrote as a 10-year- old that my dad discovered in my room, having just had my life upended and living on the other side of the world. I was wishing for a way out. Spending time with the 10-year-old me knowing I wanted a way out of life; and that was difficult.

All the emotions and realizing life is truly worth living, all of it, would not have happened without those experiences. Through introspection and leaps of faith in action, I have come to appreciate those journeys with all the setbacks and disappointments, realizing they are not final conclusions, and embrace the bruises and scars as marks of truly living.

When I heard this at the Memorial Service, and having spent time at camps for over a decade and knowing Lynne’s story which brought this camp to life, this speaks well to Comfort Zone Camp and the 25th Anniversary. Ryan Tedder (lead singer of One Republic) wrote the song as a love letter for his son, Copeland. It speaks to living a life fully embraced and engaged (no matter what the outcome), to love and live with intensity and courage even through pain, learn from every experience, with a heartfelt desire for us all to look back on our life and proudly declare, “I lived.”

When Lynne lost both her parents and saw this need through her life, and after 25 years of Comfort Zone Camps, it is truly something to be part of something where we experience what it means to truly live.

What an honor to share these stories of those impacted by this organization.

Happy 25th Anniversary Comfort Zone Camp!

And for those that want to know more about this amazing organization, including volunteering, please reach out to me.

We all bleed as one.

Until next time,

Ed